Kabbalah and Man's creation

Kabbalah and Man's creation  Sources of Kabbalah

Sources of Kabbalah

Sources of Kabbalah |

|

|

| Written by Editor VOPUS | |

KABBALAH - Etymology and AcceptationsThe word ”Kabbalah” could come from Hebrew “QUEBIL” or from Chaldean “KABBALAH”, according to certain researchers. If we consider it having a Judaic root then it mainly refers to the aspect which became accepted in Medieval Europe: INTERPRETATION, but if the word comes from Chaldean then Kabbalah defines itself as a MAGICAL SCIENCE or a SCIENCE OF MAGIC.

If we refer to the acceptation of INTERPRETATION naturally the question comes in mind: Interpretation of what? In Gnosis, through kabbalistic analysis we can study any text from any religious doctrine, because all religions are made through a standard measure, which is the Kabbalah. As we can see, in all religious texts is talked about symbols, about magical words, about numbers and all these are situated in the various currents of the Kabbalah. It is true that during the Middle Eve many of the jewish rabbis were esoterists and then they were considered the most capable of interpreting the obscure excerpts of the books that are the most difficult to interpret, especially from the Old Testament. Everything of the Deuteronomy, Leviticus, Genesis, Exodus, The Book of Numbers, all of these chapters people interpret literally and if so, they lose their significance. Tackling the acceptation of the SCIENCE OF MAGIC, we talk about a collection of esoteric teachings and mystical practices, including sacred names, invocations, numerology, ceremonial and magical elements. Both roots brought in discussion have the same translation, meaning TRADITION. It is known that the Bible has cryptic excerpts that require an interpretation, a clarification; this interpretation, in the church, is a part of the TRADITION. According to the Kabbalistic tradition, the teachings were transmitted by word by the Hebrew Patriarchs, by the Prophets and Sages (Avot in Hebrew) with the possibility that later be interwoven in the writings and the Hebrew religious culture. From this point of view, Kabbalah was, around the 10th century B.C., an opened teaching, practiced by over a million people in the Old Israel, although there are little objective historical evidences that can back up this thesis. Foreign conquests have forced the Hebrew spiritual leadership of that time, the Synedrium (Sanhedrin), to hide this knowledge and to make it secret, fearing that it would be used wrongly if it would not end up in good hands. The Leaders of the Synedrium were also worried that the Kabbalah practised by the deported Hebrews after conquests (diaspora), untended and unguided by the masters, would take the practitioner to wrong paths and to an incorrect practise. As a result, Kabbalah became secret, forbidden and esoteric for Judaism for two and half millennia. Thus we see the two spheres of the Thesaurus of the Hebrew Faith: the written teaching (especially the texts associated with the Hebrew Bible – part of the Old Testament of the Christian Bible) and the oral tradition (Kabbalistic teaching). KABBALAH – Written SourcesTwo books were the mentors of the kabbalists: SEPHER YETZIRAH and SEPHER HA ZOHAR. The first one is called THE BOOK OF CREATION and the second one is called THE BOOK OF SPLENDORS. It is assumed that they would have been written around the 12th and 13th centuries, but gather traditions that have their root in another older book called MISHNA. 1. MISHNA

Is a codification which bases itself on the written and oral law, and on the tradition or the decisions of the Judaic schools. It is the first compilation that was made of the entire Jewish tradition. Written in Neo-Hebrew, it is considered to have been made in the first centuries A.D., but obviously referring to Hebrew traditions before Christ. There are three versions of it: the MISHNA of the TALMUD from Babylon, the one of the TALMUD of Jerusalem and FREE MISHNA. Although the content of all three is the same. It was first compiled around the year of 200 A.D. by rabbi Yehudah haNasi (Judah President). It is considered the first important work of the Rabbinic Judaism and it is a major source of rabbinic religious texts. In the traditional Hebrew belief, the Oral Law (Oral Torah) is an unwritten tradition which had been given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai, which was clarifying the written part of the Law (Torah), but which was not incorporated in its text. The recent MISHNA is divided in six orders (Sedarim) each containing between seven and twelve treaties, counting a total of sixty three treaties (Masechtot), these dividing in turn in 524 chapters (Perakim) and the latter in doctrinary paragraphes or verses (Mishnayot).. The word mishnah (plural: mishnayot) can also indicate a single paragraph of the work itself, meaning the smallest structure of the MISHNA. Therefore, a number of mishnayot form a perek (chapter), a number of perakim (chapters) form a masechet (treaty) and a number of masechtot (treaties) form a seder (order); the term Shas (an acronym for Shisha Sedarim – “the six orders”) may cover the entire MISHNA. The six orders are as follows: 1. The First Order: Zeraim (“Seeds”) 11 treaties. Deals with agricultural laws and prayers; In each order (excepting the Zeraim) the treaties are arranged from the largest to the smallest, depending on the number of chapters. 2. GEMARA

Starting with the removal of the Patriarchate of Tiberias, between the first and the second century A.D., the rabbinic schools began to close, resulting in moving of the spiritual Hebrew elite and of the rabbinic tradition to the Mesopotamian area. At the end of the second century the mystical schools of Sura and Pumbedita (Babylonia) began to acquire high elevation and authority. The Mesopotamian schools asked for themselves the entire doctrinary and judicial authority. The leaders of these schools were called Gaonims. The disciples came from everywhere to listen to Rabbis for a few months, who commented especially on MISHNA. The compilation of all of these commentaries on MISHNA was called GEMARA, being considered the complement of MISHNA and the result of the work of the masters of Tiberias and Babylonia. In GEMARA there are judicial commentaries, ritualistic and liturgical subjects. The latter comprised all kinds of themes: medical prescriptions (symbolic), geography, history, legends (initiatory), fables, riddles, enigmas, examples, anecdotes, experiments etc. Ultimately, it is made a display of a high esoteric subtlety. Also, Astronomy, especially in its chronological and calendar applications, had a great importance in these studies and discussions. 3. TORAHIs the Law and constitutes the five books of Moses of the Pentateuch (penta = five, teuho = text) and by extension the ensemble of the Judaic Bible.

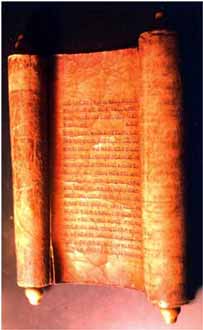

Etymologically it seams to indicate a divine answer; in general and considering that the divine answers were communicated through priests, begins to mean sacerdotal training. Although the TORAH contains law and simply translating it by “Law” means to minimize it. The best equivalent term would be “initiation” or “revelation” (of God). To the sample from the parchment that contains the Pentateuch is given the name of SEPHER TORAH. This is copied by hand by titled scribes who take special care at writing and it is used in synagogues, especially in the liturgical meetings of Saturday (The Sabbath). If durring the redacting a single character is wrong the entire parchment is thrown away but the finishing of the copying of a sample is celebrated and considered a special event. 4. TALMUD

The uniting of MISHNA with GEMARA forms what is known as TALMUD. This is the body of doctrine or the code of the Synagogue which is explained and completed through TORAH, even replacing it. For the authentic Judeans, the true sense of the TORAH, at least in the ritualistic part, is contained in the TALMUD. It is the fruit of five centuries of Rabbinic Teaching in the schools of Palestine and Babylonia. It is a work of teachers and doctors (in the rabbinic teaching). It is tried to teach and show the traditional doctrine and not to build a new doctrine, even if we can consider the result as being a more complex doctrine. The language used in the general redacting is Hebrew and Aramaic more or less evolved. The TALMUD is the ineffable code and the keeper of the entire truth of the Rabbinic Judaism. The Talmudic work has some short biblical commentaries works added and organized in independent treaties with a distinct religious character. TALMUD YERUSHALMI (THE TALMUD OF JERUSALEM)

It was prepared in the Palestinian centers of Seforis, Tiberias and Caesarea. It is written in Hebrew and certain parts in an Aramaic similar to that of the books of Daniel and Ezra. Its author is Rabbi Yohanan (199-279) the leader of the Tiberias Academy. However, the final drafting was done in the fourth century. TALMUD BAVLI (BABYLONIAN TALMUD)It contains the teachings given in Sura, Pumbedita and Nehardea in Babylonia. It is also written in Hebrew and Aramaic close to Syriac. Rabbi Asi redacted it almost entirely. It was finished in 499 A.D. by Ravina and supplemented at the beginning of the sixth century by the ones called Saboraim (opinents).

The Babylonian TALMUD includes a century in addition to the one of Jerusalem and it is five times more voluminous, being the most important of the two and it is considered the undisputable representative of the Rabbinic Tradition. The differences between the two TALMUDS are found in the various GEMARA. The subjects are treated in more profound and “more complete” form. Along with the Bible, is the known authority in the religious field of Judaism. It was the object of many commentaries, the famous ones are the ones of a French rabbi from Troyes, named Shlomo Yitzhaqi (known better by the acronym Rashi) (1040-1105); famous are also the adnotations called “Tosafist”, whose authors were mostly Rashi’s disciples (called Tosafists). The two TALMUDS were printed for the first time in Venice by Daniel F. Bomberg, the one from Babylonia, between 1520 and 1523, and the one from Jerusalem, between 1523 and 1524, the first one with Rashi’s commentaries and with the Tosafists, and the second one without commentaries. The posterior editions have generally preserved the pagination of the first ones. The TALMUD was accused of attacking the Christianism and of preaching a dangerous moral. There have been public and even solemn controversies (Paris 1242), in which the rabbis rejected the false interpretations, but who have completed with the forbiddance of the studying of TALMUD and the confiscation and destruction of the samples of the text. In the fifteenth century a german christian scholar, Reuchlin, not only that he ardently defended the TALMUD but he also promoted the study of the Hebrew writings. ZOHAR (Sepher Ha Zohar)

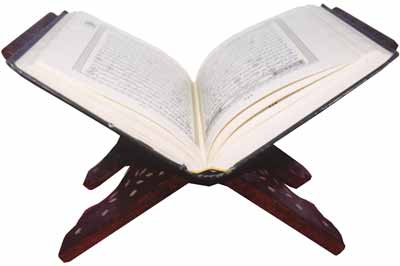

The sources of the ZOHAR are found in the fundaments of the Judaic wisdom: The Pentateuch, Prophecies, The Book of Daniel, The Book of Enoch, The Apocalypse, The Talmudin (Mishna, Gemara and Haggadah), Midrashim, the Gaonitic literature and the two books who have preceded it in the Kabbalistic theory: Sepher Yetzirah and Sepher Ha-Bahir. The manuscript of the ZOHAR must have been received the final seal in the Spanish Iberian peninsula. It contains many religious elements which must have been introduced by the rabbis from times posterior to its creation. Inventions posterior to the assumed first drafting date are also noted, for instance the punctuation. Although the exact historical datas concerning the origin of the ZOHAR are ambiguous and controversial, the fact that rabbi Moses of León (1250-1305), spanish mystic, brought it to light at the end of the thirteenth century is accepted. There is the belief that the ZOHAR was brought on earth by angels with the mission of instructing and teaching people, because they have lost their original grandeur. It is assumed that the ZOHAR reveals the secrets of God and of the Creation under the form of commentaries over the Scriptures, telling at the same time the things concerning the Human Spirit. The manuscript was written in Aramaic and is characterized by the variety of its style, which sometimes reminds us of the innocent and authoritary tone of the Bible, in some of its older passages, and in others it manifests the spirit of the new discoveries of the Middle Eve. The method of development of the ZOHAR is through speeches, histories and monologues through which it is interpreting the apothegms of the Pentateuch, of the Song of Songs and of the Book of Ruth. Generally, a large portion of the texts from the ZOHAR don’t have titles. Those that bear a title form very different lengths independent fragments.

Comments (0)

Write comment

|

| < Introduction to Kabbalah | Secrets of the Hebrew Alphabet > |

|---|

| Science |

| Art |

| Philosophy |

| Mysticism/Religion |

| Barbelo: Gnosis Magazine |